- Home

- Faye Guether

Swimmers in Winter Page 12

Swimmers in Winter Read online

Page 12

For now, there’s still work for me here in the village. I’m called on to do repairs, to help build and rebuild. As soon as I was old enough, but still a young girl, I started learning how to work with my hands.

Also, I can sing.

I was asked by the women to stay with Ella at night. I confess this was something new to me. My hands shook. Ella lay curled inwards on her sleeping mat, her eyes like cracks slit by pain watering down her face. All I could do was sing to her. When she shook desperately, taking raging, reluctant gulps of air, I sang. As she travelled restless through a long tunnel of haunted sleep, I sang softly, so that she knew someone was still with her.

I was never taught how to read or write. We have no paper. There are so few books left. I listen instead, and I work with my hands. Words are just sounds and the feeling of something. I can memorize stories told aloud, and I make my own songs like writing into the air. I build.

Still, there are dreams I have. Stories that take on life in my mind. In dreams, Ella lays me down and names things as she draws shapes across my body that I come to realize are letters—one letter into the next, as lips or limbs meet, until they form words as patterns of touch across my skin. Just by the lines she draws, soft and hard, fast and slow, I want to believe I could know all the words that matter to her most by feeling them, their different shapes: names of a sister and two brothers, a mother and a father, words from pages in a book she remembered, and those others she drew—maybe her children yet to come, mine and hers. But the baby’s name, she never speaks aloud, even though all the time it is there inside her to be said. It is the only word I know by her touch alone, not by her voice—her mouth moving silent around the shape of a sound I cannot decipher.

Sometimes, I dream Ella is looking for the baby inside of me. She would go that deep, be gone so far below, searching, holding herself inside, that when she finally comes to surface, she is breathing hard, gasping. Sometimes, in my dreams, she doesn’t know how to stop, and I can sense her diving again and again—this insistent, tender thrust of her search. Sometimes, she pulls me under too, and we search for the baby together. There, in the ebb and pull, wave after wave, when we rise, we are drenched with each other. Our bodies bearing scars, we trace and erase and retrace them.

◊

Eight months after the river stole her baby, Ella walked up behind me in the swinging heat of late afternoon. I had my bike leaning against the thick trunk of a tree and I was crouched down at its back wheel, trying to fix the chain that had come off. When I managed to pry it back on, its links would line up with the ridges of the sprocket like clenched teeth. With that solid friction between them, the chain could transfer the power from the main gear of the turning pedals to the one that propels the back wheel. This single invention of fortunate speed is one I would willingly give my entire life to.

“Never ridden one of those.”

The sound of Ella’s voice made me turn my head, my hands still on the slippery links clotted with muddy grit that also coated the wheels and the frame. I fingered the slackness of the busted chain, looked away and then back at her again, steadying myself.

She stepped closer and spoke again. “Never ridden one.”

“A bicycle,” I answered.

Ella seemed to lean limp on the air, both arms at her sides, her back straightening up against the weight of her hunched shoulders. She wiped at her face and pushed a few loose strands of hair from her eyes, the sudden motion caught by sunlight.

I looked down at her shoes, dusty and patched as these wheels I ride on. In this village, we almost religiously try to keep everything, reusing them again and again even as they fall apart.

But we possess only the tangible. What lasts in our hands makes for a slender archive. Through the scarcity of objects, how we need them. They corral us. Become something sacred. They will also abandon us to ourselves alone. I’ve seen them in their lank trails, floating the way curses ride the air, along the shore after one of the floods, long strands of debris moving in the eerie lapping of the risen riverbank. Sometimes, I see men and young mothers, still brave or hungry enough to wade in up to their chests and scoop up tattered or swollen pieces of things, precious refuse.

I have taught myself to hold onto nothing—nothing but this two-wheeled contraption of mine that knows my body better than any woman or man.

Still crouching, I kept studying the toes of Ella’s shoes, resting there in the dirt in front of me. Then I looked up at her face. Her mouth was slightly open, as though any answer or question she could think to give had already been snatched from her throat. Her eyes were dry, as she stood above me solid against the sun and the sky.

“I’ll take you out. You don’t need to know how to ride,” I said in almost a whisper, still holding the bike’s frame. Its own metal was starting to break down—it had that familiar feel, and a sour scent almost like blood. Most of the metal any of us has ever known is rusted and deteriorating. This destruction is everywhere you look, and denser the closer you get to the sea. Eventually, the bicycle will leave me.

Ella’s voice was like a bowl, round and hollow, its sides smooth. “I can’t.”

“Tonight, we could go.” I found myself persisting, and in that moment I was hardly able to look at her. Could she guess at the dreams I was having? I waited, trying to keep myself still inside.

She shook her head, doubtful.

“Ella, come out tonight. There’s no rain—”

It was her silence, with its glitter of darkness, that caught me first. In its sharpness, I thought I could sense a sudden heat.

What could I take from Ella? I promised myself nothing. What could she take from me? I told myself I had nothing left to give, except the bicycle.

“Just this once,” I said.

“I know they’ve asked you to keep an eye on me,” she said. “But why not get out of here? Find somewhere else to go?” She was telling, not asking me, as she walked away.

“I’ll come by after dark,” I called out.

What I wanted then, most of all, was to swim, to wash away my fears and the heat inside me. But since the last flood, I’ve only let myself go in as far as my thighs, before kneeling down to wash in the shallows, wary of its deeper rivulets and watery song.

That night, I went to wait for Ella behind her hut, with my shoulder to the river, my face pulled toward its rushing sound as if by a long-time lover searching for a kiss. I called out my name to the river, and all the names of the warriors of peace, now gone. The river was running luminous under the moon and stars, shining like new metal or plastic before time began to burrow them, old and ruinous, underground.

I thought of Ella the night of the flood, alone in the hut with her baby asleep. She had told me only a few details about what happened, her memories sharp as the last shards of glass we have left in the village. The rain had been coming down for hours, but no one knew how fast the waters would rise, or how far. She had been urged by others to move onto higher ground, to get away from the river, at least for the night, but she wouldn’t let herself leave. The cows were her responsibility and could not be left behind. Caring for them was the only task her brother had asked her to manage in exchange for his hut in the village. So Ella had stood in the doorway with the baby in her arms, and the animals stamping and shuddering nearby, watching the disappearing riverbank, blinking in the dampness of the air. The weight of rising water turning the ground flesh-like, a mesh of mud and grasses under the flurry of rain.

I imagined what it was like for her when the flash flood began. The river heaving up suddenly, poured heavy and sure like a gush of blood around the hut. Ella said she heard the sound of splitting and breakage strike the air, saw the low roof starting to come down. Then the water streamed inside, filling up her shelter.

The cows had panicked. Most of them went under right away, their legs splashing and kicking up mud as they sank in. Ella had moved as fast as she could, strai

ning toward higher ground, but as the waters rose and the current strengthened, she had lost her footing and went under water, and the baby was pulled from her arms.

Remembering all this, I turned my back on that watery beast of a river. Its motion was a distraction, and its sound one that I’ve come to hear more and more like a kind of salivation and swallow.

I began to sing a familiar song, just loud enough so Ella would know I was there. She came outside, and I couldn’t look away, couldn’t see beyond her. She’d rolled her pants up her bare legs past her knees, and when she came near I could smell the smoke from the cooking fire in her hair, on her skin. I rubbed the tears from my eyes quickly so she wouldn’t become a blur, lost to me.

I straddled the metal frame of the bike with one foot on either side, standing on tiptoe, waiting for her to get onto the seat just behind me, studying the shadows on the ground. She hesitated for a minute and then climbed on. I could feel the edge of her resistance but also her desire. I waited for her to choose.

She leaned in close for a minute, her face near to mine, her mouth hard, almost against my cheek, her lips there, as if to speak.

I stared at my knuckles gripping the handlebars, watching the precision of bones. Something strong. We stood together over the bicycle, hearing each other breathe. This was all there was. I reached behind slowly for her hands.

“When we get going, what we’ll need is balance. If you can, keep your knees a little bent and lifted so they don’t touch the ground. Hold onto me here.”

I rested her fingers just above my hips and they felt light there, like the glance of a touch.

“If you’ll stay sitting on the seat, I can stand on the pedals. You make the balance. I’ll make us move.”

I pushed us off, and we were going, faster with the weight of two bodies instead of one, down along the path toward the riverbank.

The bicycle is our last machine. The only energy it needs is our own. Ella put her arms around my waist as we sped up for a while, and pressed the side of her face to my back as I lifted and sank with the rise and fall of the pedals. It was as if she was both pulling me up and pulling me under, helping me to move faster and holding me down. I took the empty road, running first parallel and then away from the village, steering through the pale, cool moonlight and the thick hail of shadows. Miles of crumbling roads going to miles of nowhere. Where else could we go?

We listened to the birds and wolves across the night as we rode. Years ago, there used to be the sound of motors—that’s what Carmen must’ve heard as she rode her own bike through the light and the darkness.

But now they say there is no more oil anywhere to steal or bargain for, no more gasoline, no electricity—a word that always sounded to me like the name of a beautiful woman or a constellation of stars—and no rubber even for the thinnest of spare bicycle tires. Only wind and fire to power us, water to carry it all away.

Notes & Acknowledgements

“Sonnets to Orpheus Part Two, XXIX” from In Praise of Mortality: Selections from Rainer Maria Rilke’s Duino Elegies and Sonnets to Orpheus (Riverhead Books, 2005); reproduced with permission of translators Anita Barrows and Joanna Macy.

First and essential, thank you to Leigh Nash for publishing Swimmers in Winter, to Bryan Ibeas for editing the book, and to Megan Fildes, Andrew Faulkner, and Julie Wilson at Invisible Publishing.

I’m grateful to writers Emily Schultz and Thea Lim for being the first readers of the book when it was finished.

I appreciate the generosity of Anita Barrows and Joanna Macy for giving me permission to include their translation of Rainer Maria Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus, Part Two, 29.

In addition, I acknowledge the support of the City of Toronto through the Toronto Arts Council, and the Ontario Arts Council.

Many thanks to Carleton Wilson for publishing my chapbook with Junction Books in which an earlier version of the story “Flood Lands” appeared, and to the co-founders of Joyland Magazine, Emily Schultz (again) and Brian Joseph Davis, for publishing an earlier version of the story “Swimmers in Winter” when I was starting out.

Finally, thank you to each friend along the way and to the ones who’ve seen me through.

About Invisible Publishing

Invisible Publishing produces fine Canadian books for those who enjoy such things. As an independent, not-for-profit publisher, our work includes building communities that sustain and encourage engaging, literary, and current writing.

Invisible Publishing has been in operation for over a decade. We released our first fiction titles in the spring of 2007, and our catalogue has come to include works of graphic fiction and non-fiction, pop culture biographies, experimental poetry, and prose.

We are committed to publishing diverse voices and experiences. In acknowledging historical and systemic barriers, and the limits of our existing catalogue, we strongly encourage LGBTQ2SIA+, Indigenous, and writers of colour to submit their work.

Invisible Publishing is also home to the Bibliophonic series of music books and the Throwback series of CanLit reissues.

If you’d like to know more, please get in touch: [email protected]

Table of Contents

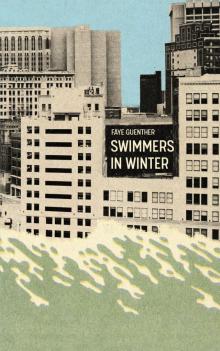

Cover

Title Page

Copyright information

Swimmers in Winter

Fight or Flight

Things to Remember

Captive Spaces

Opened Fire

Flood Lands

Notes and Acknowledgements

About Invisible Publishing

Landmarks

Cover

Swimmers in Winter

Swimmers in Winter