- Home

- Faye Guether

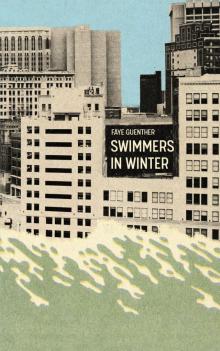

Swimmers in Winter Page 11

Swimmers in Winter Read online

Page 11

Without warning, fragments of memory cut in at the edges of her mind, looping out of sequence. She couldn’t tell where one ended and the other began. Her heart pounded like she was still climbing the hill. Sweat dampened the back of her neck, her hands wrapped into fists so tight the bones of her knuckles showed through her skin.

Carmen concentrated on breathing deeply to slow her heart rate. She blinked hard in the middle of the sleepy summer afternoon.

The birds and cicadas grew louder.

She stood up and swallowed gulp after gulp of cool water from the bottle she carried at her waist. Then, she walked slowly down the hill and through the streets back to the shelter of her apartment in her brother’s house.

◊

Carmen’s voice eventually returned. It scratched and wheezed and vibrated in her throat, but it was back.

She met with the commander and described what had happened. He did not take notes. He just looked at her.

“Why did you wait two weeks to bring this to my attention?” he asked, after a pause.

“Sir, it’s been on my mind and I realized I needed to say something.”

“The language you’re using to describe what happened is irresponsible.”

She waited for him to explain further.

“Do you understand what I’m saying?” he asked her.

She shook her head, barely.

He looked down at his desk for a moment, then back at her. “You are oversimplifying what was a complicated series of events in a high-pressure situation.”

Carmen breathed deep. “No, sir, I saw what happened. There was no reason to shoot that civilian.”

“But we can’t know that for certain.”

“Sir, I was right beside Smith. I saw and heard the same things he did. I would not have shot my gun at an unarmed civilian.”

“You should understand by now that a so-called civilian doesn’t equal an innocent. Not here, not at this stage.”

Carmen took another deep breath. “That man should not have been killed,” she told the commander. “Not that way. Not at all.”

“Smith is an excellent soldier, in everyone’s estimation.”

“He’s a killer, sir.”

“Your language is unacceptable. Absolutely unacceptable. There were numerous factors in play, some of them certainly outside your understanding or control. This is the kind of urgent situation that requires firm and immediate decision making. Smith did that. He used his judgement as a soldier to quickly assess and respond to danger. He may have saved your life in the process.”

“I don’t think so, sir. I mean, I don’t think that’s true. I believe he should be held accountable for what he did, for the wrong he has done.” Her voice stuttered. “That’s why I’m talking to you about this. And—and that’s why I refuse to work with him anymore.”

The commander told her the meeting was over.

The next day, she was given a letter stating that, based on her recent behaviour, and complaints about how she’d acted in a recent deployment—specifically, her being distracted from duty during an exchange of gunfire, and resisting orders, thereby putting other soldiers’ lives at risk—she was being discharged, and sent home immediately.

No longer fit to serve.

She’d failed as a soldier.

That evening, she slammed around the barracks in frustration, avoiding eye contact with her fellow soldiers. She knew she was being dismissed because they felt she might sabotage the morale of the unit. Disagreements among

soldiers could cause tension and interfere with accomplishing the mission.

But what was the mission? she asked herself.

She had no answer anymore.

◊

The passage of time wasn’t helping or healing her. Things seemed to be getting worse, not better. But whenever Aurora tried to ask about it, Carmen wanted only to shrug her off.

Aurora thought it might help if they got away from everything, so she suggested they go camping, at a site she’d heard about from her cousin. She would take a few days off work and they could go during the week, when there would be fewer people around.

They arrived at the site after half a day of driving, with the car stereo turned up the whole way so conversation wasn’t necessary. There was a sudden new space between them that was hard to fill with small talk, even while putting up the tent together, building a campfire. Carmen moved tentatively and deliberately, the way she did any time she wasn’t running, as if her body were bruised and tender.

That first evening, they mostly watched the water, getting used to each other’s company, resting in the silence that comes with intimacy. Eventually they crawled into the tent together and made long, slow love, turning each other over and inside out, whispering single words again and again like prayers in the dark.

The next night, when Carmen lay down to sleep, she began to shiver uncontrollably, rattling herself loose from the darkness. Aurora held her until something opened inside Carmen, and with that release, she could act again. She reached for Aurora, tearing into her where every breath was pleasure. Their bodies led them blindly, playing each other with mercy.

Carmen slept in. She spent the afternoon on the beach, sitting on a towel, studying her hands. She wiped the sweat from her forehead with the back of her hand and stared ahead. Her eyes fluttered quickly open and shut, and her lips quivered like she anticipated getting stuck on words, had forgotten how to pronounce them, was afraid of choking on them. She felt like her heart was in her mouth, and she wanted to spit it out.

Aurora, who sat next to her on the warm sand, stood up nervously and said she was going for a swim.

Carmen nodded, swallowed hard, and turned away. But then she watched Aurora strip down to her shorts, watched her wade into the water, stepping deeper until her feet couldn’t touch the bottom, watched her float on her back. She watched Aurora as long as she could, and pretended the world had disappeared.

◊

They found traces of shrapnel in Jessie’s chest, so she was to be evacuated to the hospital at Kandahar Airfield.

Carmen asked to see her, despite the growing scrutiny she felt from the other soldiers. Word had spread about her own imminent departure.

Jessie lay on the bed with bandages covering her upper body from waist to neck. Her voice sounded like a rustling in the dark, requiring a huge effort to be heard above the low-level beeps and electronic pulses of the heart machine monitors, IV drips, and the muted voices of other wounded soldiers, separated only by curtains.

“They told me I have to leave,” Carmen said quietly, studying her friend’s face for signs of distress and finding the fear in her eyes.

Jessie didn’t say anything for a minute. She struggled to clear her throat, so Carmen held a cup of water with a plastic straw to her mouth.

Jessie took a sip, then whispered, “Fine, Carmen. So leave.”

“I’ll write to you,” Carmen said. “And we’ll see each other back home.”

But Jessie had fallen silent and closed her eyes. Carmen waited for her to open them again, but she didn’t.

Eventually, a nurse walked by, looking at her critically.

Carmen got up and left the room.

◊

At the end of the summer, Carmen asked Aurora to move in with her. Aurora said yes.

She was fond of coming across Aurora reading in their apartment, or out in the backyard, which was finally dry enough after the flood for grass to grow again. Carmen loved the way Aurora peered at a book like it held a mystery, like it gave her some comfort. Carmen missed that for herself. She missed being able to concentrate on words and a make-believe world without the memories pummelling down, without images leaping in her mind, scrambling her vision and making her forget what she’d just read. Books and reading were a luxury, gifts she wanted back. She wanted her life back.

Carmen began going out on her d

ad’s old motorcycle, one he’d left her. Whenever she did, Aurora asked her to wear her helmet, but Carmen always ignored the request. She’d ride around in the wind for a while, without any destination in mind, gripping the handlebars as if she could leave and just keep going. As if it could give her escape. Ride it into nothingness.

One day, Aurora followed Carmen into the front hallway. “You can use the car if you want. I’m not going anywhere while you’re out,” she said to Carmen.

“Nah, it’s okay.”

Aurora asked her again to wear the helmet. She bent down to pick it up from where it lay on the floor underneath the coat stand, and her loose shirt fell halfway down her back.

Carmen watched Aurora’s body bending, the glimpse of bare skin. Her eyes measured Aurora’s shape, as if searching for toeholds and grips to ease her body into the branches of a tree. It seemed to her that Aurora was always escaping her clothes, always slipping out of them.

Aurora brushed her hair away from her eyes and held the helmet toward Carmen. “Please?” she said. “You know the cops will pull you over if they see you riding around here without one.”

Where they stood in the middle of the hallway, the odour of mold still lingered faintly. The heat of summer paradoxically seemed to make the dampness worse.

“Please,” Aurora said again, the helmet in her outstretched hands, the scent of the river rising in the silent space between them.

Carmen shook her head, the tiniest gesture.

“Why not?” Aurora asked.

Carmen closed her eyes, squeezing them shut. “Right before the explosion, I was wearing a helmet about the same size. I was tightening the strap.”

And then she was back there in the middle of it. She felt the helmet on her head, the sensation of the strap underneath her chin.

Stop this. You have to make it stop.

She felt nauseous. She pushed past Aurora and stumbled down the hall to the bathroom, retched painfully until it was finished, then washed out her mouth in the sink.

When she came back out, Aurora was sitting on the couch with her head in her hands. Carmen didn’t know what to do, so she began to hum. She rocked on her feet for a long minute. Then she went into their bedroom and lay back on the bed, looking up at the low ceiling. She let the air whistle and hiss out of her mouth, a long, low exhalation. Just release. Her body tense and aching all over.

Aurora came in then. She sat down shakily on the bed and asked, “What happened?”

I can’t make it stop, thought Carmen. What words are there for this?

“Carmen?” Aurora said her name like a wish.

Carmen decided she had to try again. “Sometimes it feels like everything happened there, and now I’m gone. I’ve disappeared.”

Aurora was quiet. Two fine lines ran down the centre of her forehead, finer than the ones on the palm of her hands. Carmen had noticed them before, when Aurora was concentrating hard, or when she didn’t understand something.

The last thing Carmen wanted to be was someone Aurora couldn’t understand.

She looked up at the ceiling again, squinting her eyes hard to squeeze out the tears. “Everything is still happening to me, all at once, and it’s still as bad as it was then, and it feels like it could end up killing me.”

She shut her eyes, and she bit her lip, and there was that scar inside her mouth from when she’d cut it with her own teeth while watching Smith kill the civilian.

Aurora moved closer to her and when she spoke her voice was gentle and steady. “We need—we’re going to figure this out, okay? Because this can’t be—we’re going to do something to help you.” She reached over and touched Carmen’s face gently, sliding her thumb across the wet surface of her cheeks, her temples, wherever the tears had gone. “But I need you to keep telling me about what you’re going through. You can’t just hold it in. That won’t work.”

She leaned forward over Carmen, bringing her body so near, the way she knew Carmen loved. They stayed this way for what seemed like a long time, in each other’s arms, falling into their separate dreams. Outside, the streetlights came on, pouring weak pools of illumination onto the scattered piles of fallen leaves lining the road.

Later, Carmen woke from another nightmare, and heard the baby crying in the room above them. Soon, she could hear footsteps going to the crib. The sounds from above were strangely comforting to her, and she grew calmer. In a few minutes, the baby’s cries quieted and then stopped, and it was silent again. Carmen’s fear resurfaced, her mind dragging up images and sounds she was afraid would swallow her if she closed her eyes. Starting to panic, she turned to see that Aurora was still right next to her, fast asleep, and thought about waking her. But Carmen didn’t know what to ask for, or what to tell.

Instead, she lay there in the dark with her eyes open, shaking. When she finally fell asleep it was into a dream of Aurora running beside her.

Flood Lands

Twice that I can remember, the river blossomed up its insides—moisture cleaving every surface, drips of water running like teeth along the edges of walls and ceilings. Afterwards, I would ride my bike, spraying up the muddy streets, my hands wrapped around the handlebars like a lover. The soaked landscape would pour by, a drowning village, a waterlogged dream.

Once, the river took our cattle, the group of them standing together in a haphazard circle, stamping their feet and shaking their heads at the wind and the rain that tunnelled round them. The river swept them all, a jangle of bodies into its rush and roll. It also washed away the birds, their great plumage going under like festival sails. It took our necessary objects: blades, beds, the fires on which we cooked. It stole the warped musical instruments bent by time and earlier floods, the scarce few photographs of children who are now old women and men far beyond recognition.

The river stole the one faded image of my great-great-aunt, Carmen. She was a warrior in her time, one who turned away from battle, into what life had left—and like me, she had no children. When she died, those who loved her named her a warrior of peace. I heard she used to ride a bike, motorized, without pedals to make it move. I have her name now, as well as my own that means song-maker and builder. But I find myself wondering if any of this matters now. Because the river will take it all away.

This last time, it took Ella’s baby.

Some days, when I dream of the baby, she is laughing, other days crying. But always she is floating. Her little round legs kicking like puckery fins. Her face as visible to me as the moon.

The women crowded around Ella, weeping. And then they began to cook, spreading rich smells of food into the thickness of new moisture and the billowing clouds of insects. Nothing was dry here. Nothing was without the taste of something just gone.

They say that cries of grief bring us closer to our animal selves. I have come to believe this is true. To care for Ella is to live with a wolf or a nightingale.

They also say sadness dulls the tongue. Even so, or despite this, the women salvaged what they could from their soaked provisions. They went out further, where the waters hadn’t touched, they hunted, and what they brought back they poured into their cooking for Ella’s loss. I confess my tongue burned and leaped with the flavours they created, as I sat quietly, eating with my dancing mouth, and brushing away the little stabs of the mosquitoes that clung to my uncovered skin.

I ate as if I knew this food made by the grieving women would give me the strength to sleep, and it is there that I would meet Ella’s baby in my dreams.

While my plate was filled and passed to me, collecting others’ tears as it went from hand to hand, I watched Ella. She sat close by, but her body was in knots, her face turned away. Every bite of food carried the sensation of being alive.

Over a year ago, she had arrived in our village to take over her brother’s home and care for his few cattle, while he left to find work in a larger town. She stayed a stranger to us, mostly because she was f

ierce about living on her own. I would glimpse her as I was riding my bike along the riverbank in the evenings. Ella lay on her side on a blanket, pillows of grass under her pregnant belly and between her legs, with an open book held close, reading it in the dying light. Seeing her there, resting intently in her weight on the ground, I almost forgot my legs turning the pedals. She had been working with the other women in the fields since the early morning, but now her body relaxed while her mind laboured and danced. How full, crowded even, she seemed, with something I imagined was pleasure.

It was not too long after this, and about five months before the flood, that Ella gave birth to her daughter.

Most people well enough to work with their bodies have left the village by now, headed for higher ground. I hear stories of what is out there, not so far away, closer to the sea—miles and miles of rusted, peeling, broken structures strewn across the land, hulking shapes like beached whales, their webbed plastic flesh torn away from their ribbed metal frames. Into the giant fruit of industry, the natural world is moving. It disassembles and it fills everything.

Whole cities have fallen, they say. Scattered leftovers, fragmented, flattened, earthbound. Only trees grow tall above us now.

I’ve been asked what I’m still doing here in this village half wrecked by the river, with the old people in their last days, women with young children or babies who are unable to go, and men who can’t afford to leave others behind.

My name is for song-making and for building, I tell them, so that is what I’m here for.

But to myself I think, maybe there’s a hidden part of me afraid to leave, and so my home will take me under with it in the end. Or else I will ride my bike until it weakens and breaks apart beneath me, and then I’ll walk away. The other warriors of peace are gone. I have no family left.

Swimmers in Winter

Swimmers in Winter