- Home

- Faye Guether

Swimmers in Winter Page 9

Swimmers in Winter Read online

Page 9

What are we doing here? Is this the beginning or the end of what we want from each other.

Claudia rests her head next to Jackie’s, pausing for just a minute, as if to catch her breath. Then she lifts to move her lips over Jackie’s mouth, and across her cheek again, kissing her neck. Slides her hands along Jackie’s body, over and under her clothes, as if searching for something to shift inside of Jackie through the different pressures of her touch.

“Tell me,” Claudia says again, without hesitating. “I need to know.”

◊

Jackie is sitting at the desk in the middle of the lobby again. She studies the automated security monitors, watching her own reflected expression on the screen gleam faintly back at her, the darker hole of her mouth an indistinct moving shadow. The recorded images superimposed underneath blink back as if hesitating, though via her training, she’s been instructed that there’s no time delay. The spaces captured by cameras from multiple angles fluctuate in quivers, seemingly caught in the force of invisible breaths. She can almost make out the whirring of tiny cameras positioned at each entrance to the building.

As she gets up to pace the lobby again, the looping mechanical sounds shrink, then amplify. Her world a cluster of noise.

Opened Fire

Carmen arrived home from her first tour in Afghanistan at the beginning of June. During the three-hour bus ride from the airport, she tried to focus on the familiar landscape hurtling by: tall trees nestled against the sun, pockets of deep blue water catching the light, the rusted shine of the scrap metal yards, softly ribbed soil of farmers’ fields, the empty factories with their broken windows and walls tattooed with graffiti. They all bled together.

When she closed her eyes, she saw clouds of flame and heard the sound of gunfire.

Her older brother Aaron was parked outside the station in his dark grey pickup truck when the bus pulled in. His face lit up when he saw her. Carmen approached slowly, waved a hand, and tried to smile. She climbed in beside him with her single bag, and wiped at her eyes with the tattered sleeve of her old army coat.

“That’s all you got?” he asked her.

“Yeah.”

“They don’t leave you with much, eh?”

“I travel light.”

“Good to have you home,” he said.

His face, in profile, seemed a little older. The faint sketches of lines across his temple and in the corners of his eyes made him look like their father. Carmen wondered if she should have been in touch more often while she was away. But he hadn’t written to her either. Maybe they had nothing to say to each other.

“Thanks for picking me up,” she said, keeping her voice strong. She ran a hand over her closely cropped hair.

Carmen sensed he had questions about why she was home, why she’d come back early. But he only spoke of the heavy rains. She turned to stare out the window.

“Worst flood in years,” he said. He was talking about the river, around which their town was built. “Wrecked a lot of the places along the shore. I’m glad Mom sold her house and moved to the city before the latest storm happened. I drove by yesterday. Part of the roof came down with the force of the floodwater. We were okay though. Just a little got in downstairs. Mopped up the basement right away so it should be fine for you.”

Carmen nodded. She gripped the strap of the duffel bag in her lap like it was a climbing rope and she was going up a cliff.

There were piles of ruined furniture and other flood-damaged household belongings at the end of every block as they drove along the river, heaps that her brother said just kept growing as people went about the gradual work of clearing out their property. The town didn’t provide disposal bins for everyone. Empty houses lined the neighbourhood where damage from the flood was too expensive to repair.

When they arrived, her brother’s wife, Melissa, wasn’t there. She was on the night shift at the hospital, where she worked as a nurse.

“She’s looking forward to seeing you tomorrow,” Aaron said. Then he got quiet, and looked nervous, which was rare for him. “We’re expecting a baby in a couple of months.”

Carmen congratulated him. A new life, a way to begin again.

He offered her dinner, but she told him she was exhausted and should probably get some sleep.

Alone in the basement of her brother’s house, she glanced around her new apartment. The kitchen was connected to the bedroom by a long hallway with a little bathroom at the end of it. Only two small windows, but four closets. At least there was some privacy, furniture, a door she could lock. A place to rest.

As she got ready for bed, Carmen noticed something in the air. At first, she thought the smell came from the flood damage, or maybe the mop in an empty bucket standing in the corner. But the more she breathed it in, the more she sensed it under every surface. The thin scent of burning, an aching mustiness of smoke. It clung to her body, through her clothes, on her skin, no matter how she washed. It

covered her like a sheet as she lay awake in her new bed.

◊

Carmen could hardly remember life before the military. The only thing that stood out was her father’s illness. He was diagnosed with lung cancer. She was seventeen.

Her father was a vet. He told her once, from his hospital bed, that he thought she’d make a good soldier. It didn’t matter what else she did later on, he said—the Canadian Armed Forces was a free education and a foot in the door.

She told him she would look into it after she graduated from high school. He seemed pleased.

“I know you’ll make me proud,” he’d said, his eyes still bright, as he reached up to squeeze her shoulder.

When Carmen started training the next year, she felt like she belonged. She could channel her will into being a soldier, into acting the part. She wrapped herself in camouflage and grew accustomed to the genderless feeling that filled her when she wore the heavy uniform, held the weapons in her hands.

Later, she wondered if it had been a way for her to hide. In the army, there were fewer ways to meet women—there were far fewer women than men on base to begin with—and the opportunities she had, she didn’t take, though they occupied her mind. The guys mostly left her alone. A couple of times, she’d needed to defend herself, in another form of combat, being on the offensive and defensive at the same time.

Soldiers are told that death is a possibility one has to accept. But as Carmen went through the months of training, she didn’t think about being shot, or shooting other people. She thought only of shooting the gun. She focused only on the weapon in her hand, the targets on the range, on the movement of gear and supplies, on the presence of her fellow soldiers.

Training, for her, was about repetition and obedience, and following orders meticulously. But it was also about pushing her body as far as it would go, and discovering it could go farther. She watched action movies and imagined that she was in them, that she was becoming indestructible. Not Carmen in the uniform, but Carmen as uniform, as soldier.

In time, she came to feel that there was nothing underneath.

◊

Now that she was home, Carmen felt separate from the slow-motion routines of civilian life.

She had to force herself to leave the apartment. Every couple of days, she would go for groceries, so she could have something of her own to eat. During the warm summer evenings, while her brother was doing shift work at the factory, she would sit on the front porch with Melissa and talk about the pregnancy—Melissa was seven months along—or chat about the changes in town over the past few years.

One evening, Melissa suggested she check out the local community centre, to do something again. “Aren’t sports your thing?” she asked, like she already knew the answer.

Carmen nodded, grateful for this moment of calm, as though everything was ordinary. “I guess it would be good to get out of the house,” she answered.

All around them, the dusk we

lcomed the darkness.

“Sure,” Melissa said, taking a sip of tea, watching her.

“I wonder if there’s a running group,” Carmen continued. “I’ve been finding it hard to concentrate lately, but running helps.” She glanced at Melissa quickly. Had she said too much?

But no, her sister-in-law was listening to something else, laughing quietly with her head tilted to one side. “Feels like the baby is wide awake and kicking,” she replied.

They sat there for a while longer, their palms against the taut skin of Melissa’s round belly.

◊

Carmen’s artillery unit was flying to Kandahar. Before they left, their commander told them that what they did with their time on Earth was of greater importance than how long they spent on it, that the world was watching, that their actions could change history. Carmen felt more powerful than she ever had before in her life.

“Think about where you place your trust, and pay attention to your conscience,” their commander said. “Know that you are experts on the use of force and violence when necessary.”

No one had addressed Carmen as an expert before. No one had spoken to her about such large responsibilities.

There was only one other woman in her platoon. The two of them tried to stick together. Jessie was a woman who came on strong in conversation, both impulsive and direct, often tripping over Carmen’s shy, sly delivery. She had a buzz cut, one she’d given herself, and she convinced Carmen to do the same. Her face was small and expressive. Emotions moved like lightning across it.

One day, shortly after they met, Jessie said, “You know those fucking military ads at the bus stop and on TV, with the girls in army fatigues holding wrenches, or getting out of military helicopters? That’s what brought me here.”

“Did you find them?” Carmen asked her.

“Who?”

“The girls.” She was half joking, half serious—maybe even flirting, if she was honest.

Jessie didn’t get it, just kept icing her knee. She’d busted it earlier in the day, when one of the guys shoved her down during the outdoor drills. “I have no idea now what I would’ve been if I’d stayed away from this,” she replied, eventually.

◊

The running group at the community centre met each morning at eight, Monday to Friday. Despite being weary from lack of sleep, Carmen tried to show up every day of the week. One of the first mornings, as she was glancing around at the small crowd, she saw a girl bending down to tighten the laces of her sneakers, her short dark hair falling across her face. When the girl stood up, Carmen noticed that she didn’t make eye contact with any of the others in the group.

The dark-haired girl was there most mornings. Her name, Carmen discovered, was Aurora. Carmen thought of talking to her every morning thereafter. But running didn’t exactly invite conversation. Plus, Aurora seemed to be on her own page, seemed like someone who was used to being alone and didn’t mind it. She was faster than Carmen, usually at the front of the pack, her long legs kicking up and down at the earth, as if with every stride she found more reason to run, more untapped energy.

What was someone like her doing in this town?

◊

Carmen had no idea what it was like to call Afghanistan home. To grow up there, to know it intimately, the way a person knows the place of their birth even after it has been stolen from them. Packing up her old bedroom in her mother’s

house before leaving for her deployment, she’d found pictures of Afghanistan in old issues of National Geographic collected when she was a kid. Taken more than two decades ago, they depicted mountain ranges, valleys, deserts and dunes, lush orchards, rivers, jungle-like fields of wheat, opium, and marijuana. As she looked at those photos, she fantasized about learning Pashto. She wanted to understand what the people were saying to her, thought it would somehow make her less complicit in the cruelties of war.

But when she came to know the country, it was only as a soldier carrying a gun.

She kept her head down when she heard the racism directed toward Afghan people by other soldiers, pretended

to ignore what they said, the same way she did when she heard them talking about queers. She was accustomed to hiding in order to get by, knew how to turn away and shrug off the words, the derision, knew how to keep her expression controlled and flat. She hoped she could rise above it—without standing up or speaking out—if she was a good enough soldier.

After a few weeks, Carmen and the other soldiers were ordered to engage in routine patrols around the villages, outside the wire, which meant going beyond the borders of the large basecamp and into areas where they would need to be prepared for potential combat.

Real combat, when it happened, was nothing like she’d imagined. It always happened so fast, without a chance to adjust or to reflect. Anything could happen in a breath: on the inhale, bullets fired; on the exhale, someone wounded, someone dying.

Carmen would find herself lying in the sand or behind buildings along with the other soldiers, waiting to attack invisible enemies. They would press themselves to the ground under the heavy weight of their gear, strung out with nervous energy. Some of the guys smoked, some would dry heave into the sand, some cried to themselves, the sobs digging deep in their throats, and some even started firing their weapons crazily at their own dread.

How she survived, she did not understand.

◊

Carmen finally caught up to Aurora about two weeks after finding out her name. It was near the end of a run, when they were both breathing hard, and looking ahead instead of at each other.

She only learned later that Aurora had slowed down on purpose, and had done so against her better judgment.

As they headed together along the battered shore, Carmen mumbled an introduction that was both a little out of breath and jumbled by her feet hitting the ground. She was really starting to feel the hunch of her shoulders, her upper body boxed tightly, wound up like a spring, as if she were getting ready to throw a punch.

Aurora spoke to her then. There was barely a question uttered between them—and barely an answer—but somehow they made a decision to meet, and in the brief euphoria following the run, they set up a place and time.

They’d go for drinks. That was all.

Afterwards, despite the fact that it had gone so easily, Carmen thought she had been too forward. Too obviously out of practice. Also, maybe, that she was finally losing her mind.

◊

Some of the Afghan elders who Carmen met during the combat mission insisted through their interpreters—terps, the soldiers called them—that the Canadian and American soldiers were as much the enemy as the Taliban. That it was their presence that caused the killing, the vandalizing of their homes, the disruption of their lives. That it was the soldiers from the West who were trapping them in the middle of a conflict in which the price even of speaking out was terrible.

The longer Carmen spent in Afghanistan, the more this reality began to crowd her thoughts. It threatened to break through the surface of what she had accepted as truth, until every step she took felt false, and every command she took direction from felt like a lie.

◊

For the first time since she’d come home, Carmen found herself sitting in a crowded bar. She pulled at the pale fabric sticking to her neck in the summer heat. She knew her T-shirt hardly fit her, but she’d rushed to get ready and the shirt was the only clean thing she could find to put on.

Carmen tried to remember where it had come from. She must have gotten it when she was smaller, maybe as far back as high school. It had been in one of the boxes her mother had left with Carmen’s brother when she moved to the city. Most of what Carmen found in those boxes, she didn’t recognize at first. But because she didn’t have many civilian clothes left, and had no money to spend on a new wardrobe, she wore whatever she could find.

The bar continued to fill up while Carmen waited for Aurora. A gr

oup of girls sat down at a table next to hers. She hoped she didn’t know any of them. Luckily, most of the people she’d gone to high school with had moved away to find work. The older folks, on the other hand, she was especially wary of. They always felt they had the right to ask questions about what had happened to her, the soldier’s daughter, the fighter.

Carmen and Aurora had agreed to meet here, as opposed to any other bar in town, because it was the biggest one, and because Aurora had heard from her cousin that it was a more open kind of place.

Aaron agreed, when she’d mentioned to him that she was meeting someone there. “That’s a good choice,” he said, looking up from the kitchen table where he was sitting, going through the household bills. “Of the four in town, it’s probably the best one. It had one of those rainbow flags in the window for a weekend in June, last year. I mean up on the Friday evening, and down by Sunday night, but still.” Aaron lifted his hands, which were a lot like her own, and smiled, like he wished he could give her more.

Carmen didn’t know what to say. So she waited, because it seemed like he was going to ask her a question.

“Have a good night,” Aaron said, turning back to the bills on the table.

Despite all the assurances, she found she was getting some hostile second glances at the bar. She guessed it was because of her buzz cut. And this shirt—what had she been thinking when she put it on? There was a printed colour photograph on the front, of two tigers facing each other in profile, nose to nose. Below the picture were the words Wild Cats scrawled in a jagged black font. The sleeves were especially small at her shoulders, showing off muscles still thick from training.

Carmen tried to remember the way lifting weights made her feel: like they could prepare her for anything.

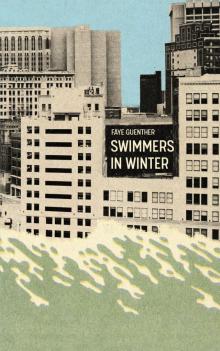

Swimmers in Winter

Swimmers in Winter