- Home

- Faye Guether

Swimmers in Winter Page 7

Swimmers in Winter Read online

Page 7

This had all happened before.

If I stay still like this, will they leave me alone?

Above her, a group of other thirteen-year-olds circled, mostly girls, laughing. Beyond the mustiness of the ground, the air was full of their scent: vanilla perfume, cigarettes, and cinnamon-flavoured chewing gum.

You fell, or they tripped you as you tried to get away. Again.

All Jackie could concentrate on was the hurt.

She reached to her face. It was the place they could most easily find her shame, no mask ever thick enough or large enough to hide her.

My glasses are gone.

Down on the pavement, she was eye level with their black boots and bright sneakers. It was hard to see any distance without her glasses, but she could feel their lean storm gathering. The laneway, a shortcut to the back of the recess yard, was quiet otherwise.

Wherever she went, they followed. The thing they hated most seemed locked within her.

I can’t say what it is.

She believed they might even be willing to break her open, to reveal what they couldn’t stand to see. She knew what they would dare, beyond the burn of their words.

I’m afraid they’re going to hurt me worse.

“Jackie?”

Her name said with such heat. She flinched.

Jackie moved her hands over the blurry ground in front of her. How could she find her glasses when she couldn’t see anything properly?

There was laughter as she scrambled to try and sit up. She felt a kick from behind that landed on her left side, just below her heart. The force sent her back to the ground. A sound left her lips before she could stop it, something between the heaving of prayer and a sob of anticipation.

“Jackie?” the voice said again.

Someone else mimicked it, and giddy laughter rang in response.

Suddenly, a figure hurtled into view, almost tripping over her. It leaned into its velocity, on the edge of falling, legs bent, arms out as if hanging from the air, and let out a shriek—a weird, garbled cry of jubilation or pain, the kind of sound only a girl can make.

The crowd paused.

To them, what they were doing was just a game. It was supposed to be funny. Forcing Jackie to realize there was something wrong with her was just a way for them to deal with ordinary boredom, to slap away the constant biting embarrassments of their day, to figure out what they meant to each other.

But the interruption, the deranged sound, seemed to suddenly bring the moment into focus: its messiness, the ugly feelings.

They didn’t think they could laugh at this part.

The stranger lurched toward them, howling, her fists everywhere.

They raised their arms to shove back at the girl. Pushed her hard. “How dare she. Hit her. Get her. She’s crazy.”

Jackie wrapped her arms over her head and tried to get up onto her knees. She felt another kick land at the centre of her ribs, not as sharp as the earlier one, but with enough impact that it slammed her back down to the ground. She rolled into a ball.

Something wet landed on her face. Don’t let that be blood. But what she wiped from her cheek wasn’t red. Spit from someone’s mouth.

The fighting girl stood right above her now, throwing fast but messy kicks and punches. The crowd began to back off.

Someone was crying, telling Jackie she’d be in trouble.

They were fighting so near to her, Jackie could hear their heavy breathing, their feet clambering around her.

Then, from down the lane, the school bell rang, and as if the sound were a spell that could erase chaos, the space around Jackie emptied out.

But the fighting girl remained. She was breathing fast, kept turning to see if anyone was still hanging around for a fight. When she crouched down, her hands remained aloft, as though she wasn’t sure where to put them with the fighting done.

“They’ve all left,” she said. “That girl, Amanda, likes to fight me. I hate her.”

Jackie tried to sit up. The whole side of her body from shoulder to waist was burning, and this girl in front of her was a blur. “My glasses.”

“Hold on.” The girl moved away for a minute, on her hands and knees beside the parked cars. Jackie hoped she’d leave soon.

Please let me go. Leave me alone.

The girl returned. “They were behind the front tires over there. They don’t look broken.” She handed the pair of glasses back, and as she did so, their hands brushed.

Jackie pulled away, as if any contact could lead to cruelty. She peered at her glasses. There was a scratch across one lens, but like the girl said, not wrecked. Once she put them back on, the world shifted into focus, and she could finally see the face in front of her in detail.

“Are you okay?” the girl asked, running her hand through her red curls, pulling them back off her face. There was swelling on her cheek, around a cut that would soon become a dark bruise. The girl’s knapsack, though jostled, was still on her back, but the collar of her shirt was torn, and she held her hands in front of her as if they’d been burned, flexing her wrists and fingers, blowing on her fingertips.

“They sting,” she explained, as if Jackie had asked.

There were bright colours under her nails. Paint.

She’s so small. How did she scare them off? Jackie thought.

The girl seemed newly seized with urgency. “Can you sit up? We should get out of here.”

Jackie looked down at her jeans and sweatshirt covered in dirt. “My side is killing me,” she answered.

“Move slow, okay? I’ll help you stand.”

Jackie tried to raise herself, to push against gravity. She had to lean on the girl’s shoulder to get up.

“Let’s head to the park,” the girl said, pointing down the street, and they started moving. Jackie limped from the pain in her ribs.

The girl continued to talk, hectic and casual at once. “Next time, you can’t let them take you to the ground.” She looked ahead and practiced a long glare that was punctuated by the open cut on her cheek, wet in the sunlight. “Because what they do to you will be a lot more bad if it comes from above.”

Jackie dabbed at her forehead with the back of her hand to check for bleeding. “I was trying to get away.”

“Yeah, that’s hard.”

“It always happens.”

“You should try martial arts, like self-defense stuff. You know, karate. They teach a lot of things there. My cousin takes lessons at a gym. He showed me some of the stuff he knows, like how you have to keep your eyes at the exact same level with your attacker’s eyes. I bet martial arts would be good for you.”

Jackie thought of a karate movie she’d seen a few years ago in the theatre. “It seems like an almost impossibility,” she said, wincing in pain, her jaw sore and her lips dry.

The girl leaned in close, her curls almost touching Jackie’s face, her wide eyes blinking fast above her swollen cheek. No one got this close to Jackie anymore, not even her parents. At thirteen, she was already keeping to herself, building little bunkers of privacy wherever she could, running from one to the next. So tired, without relief, she’d even begun to imagine killing herself, if not for the fact she’d miss her little brother.

Jackie was in too much pain to pull away. Mesmerized by the girl’s intimacy, she awaited the mockery that always came whenever someone got this close. She swallowed hard against the sharp ache in her chest.

The mockery did not come.

The girl laughed. “I like that. An almost impossibility.”

Years later, they would still use that phrase to describe to each other the things they wanted.

The girl checked again to see if they had any followers, anyone coming back to finish the fight. “My cousin’s gym is where he goes to learn the martial art moves,” she continued. “He’s older than us, in high school. But I’ll find out what the gym is called

for you.”

She stopped, as if something just occurred to her.

“Do you remember me?”

Jackie didn’t.

“I’m Eva. I drew your portrait in art class last week.”

Remember.

Jackie took off her glasses again to wipe her eyes, and was ashamed to feel them filling up. She needed to get away.

“There’s public washrooms in the park where we can get cleaned up.” Eva put her left arm through Jackie’s, like a rope tied tenderly, and they shuffled along while the tears slipped down Jackie’s cheeks. “Does anyone know this is happening to you?’

◊

Jackie hears her friend’s voice as if it is right there beside her.

She turns quickly, but no one’s there.

The polished interior of the lobby shimmers at her, lit up like an exhibit in a museum. Every night, she studies the dustless, potted ferns, as if to burrow into their synthetic olive-green glow. She imagines diving into the smooth dove-coloured couches that look like they’ve never held a body, illuminated by pools of white on white. When she peers down the centre of the lobby, she can see the waiting elevators, closed for now. Their copper panels beam as she approaches. Nothing else moves. Then her eyes overflow, and she covers one and then the other with the back of her sleeve. Blinded.

◊

When Eva and Claudia moved in together, Jackie hung out regularly in their east-end apartment.

Sometimes she would stand in Eva and Claudia’s bathroom, the door closed, trying to decide whose things belonged to who. Shea butter lotion in the cupboard: it reminded her of Claudia’s quiet presence in a room, the smoothness of her hands even though her fingers were always flecked with little burns. The curly-hair shampoo on the edge of the bathtub: Eva’s. Jackie opened the bottle to breathe in the scent.

Once, Jackie found herself in their bedroom, looking into a small silver enamel jewellry box with a missing lid. Inside were Eva’s golden hoop earrings, beautiful ones that danced beside her face as she moved.

Eva caught her snooping. But instead of getting upset, she shushed Jackie’s awkward apology and offered to lend the earrings to her. She dangled them delicately from her outstretched fingers, as if handfeeding a bird in the park. Jackie thought she saw a flash of recognition in Eva’s expression then, wondered if Eva saw her differently in that moment: as someone more ambitious and wanting than she let herself appear.

“No thanks,” Jackie muttered. “They’re yours.”

Eva smiled. “Well. Anytime.” She put the earrings back inside the box, which she could not close, and steered the Jackie out of the bedroom, her right hand balanced, almost tentatively, on the middle of Jackie’s back.

◊

The more time she spent with them, the more certain Jackie became that Eva and Claudia were night and day.

When she and Eva met as kids, Eva already had a kind of high-wire momentum, a sudden velocity she would never grow out of. In fact, it had only accelerated since then, with or without a destination. Eva was lucky to have painting in high school, access to space and supplies in the art room, a teacher with bright eyes who floated in and out and kept giving her work attention. In those years, Eva still had a means of survival. But after high school, after she gave up painting, she seemed more and more to be searching for somewhere to put her focus.

Claudia, on the other hand, was solid and reflective. Something always seemed to be happening under the surface. The library books stacked in the living room were all hers; Jackie would flip through the pages, searching for a way to decipher what Claudia was thinking about, memorizing the colours and images on the covers as if they were clues. All that said, Claudia wasn’t shy—she could stare you down if she wanted. She just didn’t need to say much, preferred to listen, to stand back and watch. Jackie told her more than once that she could’ve been a security guard too, if she wanted. And Claudia would always shrug, but it seemed like she didn’t mind the compliment.

Back then, Jackie never saw her smile big, or laugh in an opened-up way. Never, except in Eva’s company. And though Jackie would eventually learn how to get Claudia to do both, only Claudia can say whether it feels the same.

◊

Jackie remembers the last time she saw Eva. It was five years ago, in February. Eva had called her up and asked her for coffee.

“I feel like you’re disappearing from me, Jack,” Eva said, laughing, in response to Jackie’s silence on the line. “Give me a sign.”

True, it had been a long while since they’d really talked, just the two of them. The last time Jackie could remember was when Eva asked her, privately, to borrow money. Jackie lent some from the little bit of savings she’d added to her bank account. It was money she needed to get back soon—her savings were reduced to almost nothing, no buffer— and Eva still hadn’t returned it.

That should have been enough for Jackie to get in touch, to follow up with her. But the truth was, it had become impossible for Jackie to be alone with her old friend. Had been that way for months.

The reason for it was difficult to face. She had to float in it for a while, her mind treading water, consuming most of the energy she had. Only after could she finally admit to herself the indisputable truth, something that she couldn’t tell her friend: Jackie couldn’t be alone with Eva because she wanted to be with Eva. Everywhere and nowhere at once.

How could it not have always been this way? Jackie asked herself.

I remember who you are, what you started with.

I remember the colours all over your jeans and under your nails, from painting the night before.

She remembered, from back in high school, the look on Eva’s face when they leapt high, together, into and out of trouble. And a little later, older, how they’d come together to describe the different, brief lovers they’d found, each man and woman. Always coming back to each other.

Eva, she realized, was the only person who, in greeting or in goodbyes, would wrap her arms around Jackie like she was climbing the side of a mountain. And yet somehow, there would still be so much room to breathe, as if the act of closing the space between them opened up so much more.

How could she not have noticed before the details of how Eva’s body felt against her in those embraces, humming and loose? Not have noticed Eva’s hair and skin and scent spread across her shoulders? How Eva would, with one arm still reaching round Jackie, lean back to look into her eyes? How Eva would then pull closer, as if her life depended on it?

And now that Jackie understood what it was to be held in Eva’s arms, she wanted it more. She could not deny it, even if Claudia was standing there watching, meeting her eyes.

Which was why—despite her better judgment, and despite it being her only day off that week to do anything beyond eating or sleeping—Jackie had agreed to meet with Eva. Only for Eva would she carve out this time from the small plot that her life outside of work had become.

The cafe was crowded that afternoon with people looking for respite from the cold. Around the wide room, the windows were fogged up. Jackie watched the steam rise from Eva’s cup, found herself looking at Eva’s bare arms on the table between them. Light glanced off the rim of a glass where Eva’s lips touched, off the inclines of spoons, off the crystal granules of sugar Jackie wiped away, palm down so they stuck to her skin, off the pockmarked wooden tabletop she rubbed at with her thumb. Words hovered, adrift, between them. Maybe they were both unsettled from the frozen winter afternoon, shot through by the sun, sitting there waiting for somewhere new to land.

“How’s the new job going?” Eva asked.

“Good,” Jackie answered proudly. “Full time for six months.” She said it like a promise.

“You look happy,” Eva told her, and smiled.

Her smile—Jackie thought she’d seen it every single way. She knew that this time it was a smoke signal, not a reflection of how Eva actually felt.

Just what were they doing there, alone together, without Claudia?

Jackie asked, “How’s it going at the diner?”

Eva laughed, a short howl that startled the older woman sitting alone at the table next to them. The woman peered over her newspaper, fingers catching at the black-and-white headlines.

“I think I’ll be quitting soon. I’ve got to try for something else. You know how it gets when you’re ready for a change. I need it.”

Was she speaking of more than her job? Jackie wondered.

“Please don’t tell Claudia. I haven’t talked to her about leaving the city yet.”

Leaving the city.

The words felt abrupt, almost violent. A hit that hadn’t landed yet.

Jackie stared. It felt like they were standing together in an apartment with all the furniture removed, empty and waiting. Just the two of them, fumbling back to where they’d started, back through all the times they could have disappeared from each other—but didn’t, despite the odds.

It had always been hard to say who needed who more.

“This place,” Eva continued, stretching out her arms, “all of this fucking city in winter gets me down.” Her small hands hung in the air, fingers spread as if conducting light.

Jackie fixed her gaze on Eva’s hands, so as to not catch her eyes and possibly betray herself. But maybe that was what Eva had been waiting for—to see if Jackie had learned to fight. If she had figured out yet what she was fighting for.

Did you find the answer?

The charm bracelet on Eva’s wrist, a gift from Claudia, slid down her raised arm.

“Where could you even go?” Jackie wondered, as she asked, if it was a mistake to do so.

Without me, where could you go?

“What kind of question is that?” Eva brought her hands back to the table.

“I don’t doubt you’ll be okay. I have no reason to doubt you. I’ve known you for so long.” She looked away, then back, laughed reluctantly. “And you know me better than I know myself.”

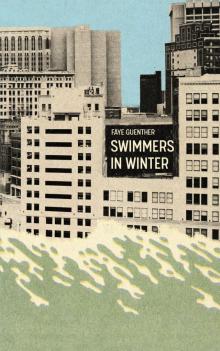

Swimmers in Winter

Swimmers in Winter