- Home

- Faye Guether

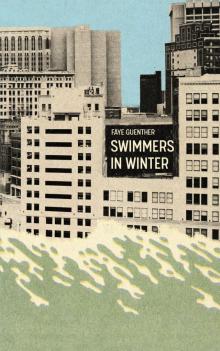

Swimmers in Winter Page 4

Swimmers in Winter Read online

Page 4

“You can see I’m short-staffed today,” he said, “so you’ll have to handle the lunch rush.”

Maybe you didn’t notice we just got through breakfast, I thought to myself.

“No problem,” Claudia said.

“Keep the customers’ orders coming steady,” he warned her. “No gaps.”

After the lunch prep was done, those of us working in the kitchen decided we would start taking our breaks as the orders began coming in, instead of waiting until it got real busy.

The others took their turns first, leaving just Claudia and me. I said to her, “You’re so quiet today.”

It was only half true. Claudia always seemed quiet.

She looked up at me as she made grilled cheese sandwiches, buttering six slices of bread on both sides, moving in a flash, two fingers red from a recent burn.

“I’m concentrating,” she said.

I smiled. “You’re not bored?”

“I don’t get bored.” Claudia put down the knife and reached for the pan.

“Really?”

“No. There’s always something to do.”

“You mean in this job?”

“In this job. In life.” She turned back to the sandwiches.

“Huh.” I thought about it for a minute. “It’s funny to hear someone say that. I think a lot of people would get bored.”

Her focus was back on her hands now. She laid the sandwiches out with intention, side by side, neat in the pans. “You know what it’s like when you’ve got all these things to figure out, like everything is piling up and you can’t get to it?”

I thought I understood. I tried to, as I stirred the big pot of cream of tomato on the back burner. “So what’s on your mind?” I asked her.

“Memories, I guess. Nothing bad. It’s just that they never go. There’s a pile of them there, but they’re all out of reach.”

She frowned as if in apology, but her eyes were bright. I wanted them to dare me.

“Like songs that get stuck in your head?” I tried.

“No, not really like that.” She laughed warily. “Because you can sing a song to yourself, and it’ll eventually disappear. Get replaced by another one, I guess.”

Another order came in. Tuna salad. I went to the fridge to get out the bowl we’d prepared that morning, and extra mayo. She hovered the spatula over the pan of grilled cheese, a rare moment of stillness. I went and stood beside her, watched the butter and orange cheddar sizzle with heat.

This was basically against the rules. We were always to be doing something. Not standing still. Not waiting.

She began to flip each sandwich, one at a time, briskly, with perfect aim. “These memories,” she continued, “there’s no story I can turn them into and retell. They’re just flashes. Like, quick flashes. And then they’re gone. Still in my mind somewhere, but I’m always getting further away from them.”

“Try thinking forward,” I said to her. “The past can wait because it’s done. Think about the future instead. No one else is going to do that for you. Don’t ask for permission either.”

Don’t ask for permission was a phrase I’d found in a magazine at the grocery store, or maybe someone had said it on television. I tried to make the words sound like they belonged to me.

The sandwiches were ready, so Claudia headed for the deep fryer. Almost every order came with fries.

I thought maybe she hadn’t heard me, so I tried again. “Sometimes you have to take chances to get ahead.”

◊

Later, I would offer her my own confessions—all of them in the past tense. As though my memories were shells that contained oceans. I told her things then that I haven’t shared since. It was a relief, to turn myself inside out for her, heart in my mouth, then trail off.

I did that with Claudia. I told her the things I wanted to hear.

◊

That was how it began. Some worry or wish, which led to another, until they flew around my head like birds. It got harder and harder to hold them in, hold them down. I would rub my eyes to get rid of what fluttered there.

One day she asked me, over the wet rattle of dishes, what was wrong.

And I knew what it was. Not something wrong exactly, but something new.

I looked at her.

Claudia was taller than me by half a foot. She lifted her dripping hand from the sink to my curly hair and gently pulled. “You’ve got a bird’s nest up here,” she said, laughing, as a flicker of water mixed with soap suds landed on my face.

◊

I didn’t know much about cooking when I first applied to work there.

The manager looked me up and down. “Ever work in a kitchen before, Eva?” he said.

I lied about working in three others before this one.

He kept squinting at me, so I crossed my arms over my chest and focused on a poster just to the left of his face, an image of the CN Tower puncturing the sky, with the words See you at the top! in punchy gold letters. But his eyes continued roving until something fell in the kitchen and he turned toward it, cursing.

Broken free of his attention, I reached for the strap of my shoulder bag and readjusted its weight. It held a two-litre carton of milk I’d found on sale, cigarettes, and some day-old buns and pastries from a shop on the corner. I was all out-of-pocket then, and betting a place like this would have leftovers at the end of the day, leftovers they needed something to do with. That’s what made me walk in when I noticed the Help Wanted sign in the window.

“Okay, sweetheart,” he said. Then his eyes were on me again, so I met them, and he looked away. “We’ll give you a try. Be back here tomorrow, seven a.m.”

He never did say hired, but I knew that I was.

Not long after that, I realized I was the only girl working in the kitchen.

◊

A month after I started, I saw the hiring sign was back in the window. Maybe business was picking up and they needed extra help?

I found that possibility hard to believe.

The kitchen was empty by the end of my shift. The morning and lunch rushes were over, and most of the other staff had gone on their breaks, leaving me to clean up before I could slip a few things in my bag and head home. I was leaning for a minute on the counter—to rest my arms, sore from the dishwashing and from carrying the piles of plates—when I heard the jangling of the bells on the front door. Then a voice, solid but cautious, in a girl’s deep pitch.

I knew the manager was still standing by the cash register at the front of the restaurant, counting change. I wanted to listen, so I moved to stand just inside the entrance to the kitchen. I was worried about being replaced. I guess I was also trying to look out for her. Just in case. I didn’t want him to try anything with someone who wouldn’t know to be careful.

He told her he already had one pretty girl, and asked what he would do with two.

I caught a glimpse of her reflection in one of the mirrors along the walls that made the room seem momentarily endless. She cocked a smile: sudden, sure, and a little hungry.

I recognized it before I knew her.

Maybe that smile was what the manager thought he was looking for. Or maybe he realized, from the resumé she handed over, that she actually had enough experience and could find her way around a kitchen.

One thing I know for sure is that he underestimated her from the beginning.

“Eva will show you around,” he said. Then he paused and called out to me. “Eva! There’s a new girl starting today.”

And suddenly she was walking toward the kitchen. Tall, with sloped shoulders, her hands in her pockets. I moved away so it wouldn’t seem like I’d been listening at the doorway the whole time.

She barely looked at me when we said our hellos. Instead, she surveyed the space as if she could see some possibility that wasn’t visible to me. I wondered what she thought of the state of the kitchen. Its c

haos that I was supposed to wipe clean.

Even then, I was already craving suspense, when it was Claudia I was waiting for.

I watched as she forced herself to accept a hairnet from the cardboard box. Then I handed her an apron—a spare one I’d yanked from a hook in the broom closet, one smelling of ketchup and the laundromat—and told her that it would be deducted from her first week’s pay.

That was when she finally looked right at me, down from her height, with those brown eyes of hers. The kind of eyes that go on and tell you something and then almost immediately look the other way in case you happen to hear what they have to say.

“That’s messed up,” she said quietly, shaking her head, “to have to pay out of our own pockets.” She frowned.

I thought maybe she was trying to figure out how she could afford it. “Tell him,” I said.

She didn’t. But I noticed that she would treat that apron as if she’d earned it, as if it was made for her, even though any of us working there could’ve worn it.

Later, we stood across from each other at the counter, rinsing, peeling, and chopping carrots and potatoes. Their moist surfaces glistened in the fluorescent lights.

“Like a sauna in here, right?” I said to her. Claudia wiped the wet edge of her forehead and jerked a thumb toward the end of the kitchen facing out on a crumbling parking lot behind Yonge Street.

“Hotter in here than outside. Even with that back door propped open,” she replied, as if it was a secret she was tired of keeping.

I wondered how long would she last.

◊

There were so many rules around us, spoken and unspoken, and we were both used to being told we had broken them. It was something we shared from the beginning.

But still, it grated on Claudia. Getting told she’d done things wrong. I think it was because she paid attention and noticed the hypocrisies, always deciding between whether to point them out or to prove herself despite them.

The thing is, except for when she was cooking, everything Claudia decided to do took time. A lot of time. No matter how fast life was moving around her, she moved slower.

I warned her that there are only so many opportunities, and they tend to change and disappear if you don’t make a choice and run with it.

The two of us took the most blame under the manager’s watch. He liked strong words and he would use them to get a rise out of anyone. More than once, he told us he should let us go.

One Sunday morning, when we were hungover and chopping potatoes for the deep fryer, he came in and saw that my hair was down around my shoulders. I tried to sweep it up in a bun when I heard him coming, but it was too late.

“Listen. You listen to me, now,” he hollered. “There’s no way I’m gonna let this kitchen get shut down by some goddam inspector because of you. You better clean yourselves up if you want to keep this job. I’ve said it before. I don’t want to have to say it again, right?”

Our eyes took in the floor and then the ceiling, flinching at the clang of pots and pans, and at the bright fluorescents. I felt a sense of tired relief when he left.

I told myself that he wouldn’t have the guts to fire me then and there because he still needed me, at least for that shift. I also told myself I didn’t really care either way.

Claudia, however, looked disappointed—maybe in me, maybe in herself.

I wanted to ask her: Why would you expect anything else from him?

◊

A week later, I decided I wasn’t going to seal my head in a hairnet anymore. The job didn’t matter to me. I would not give it my loyalty. Instead, I wore a baseball cap into work, my hair pulled back tight inside it.

It was early morning. I found Claudia already there, alone, the first one to arrive in the kitchen. To my surprise, she seemed almost betrayed when she saw my cap. And maybe it was a kind of betrayal: of what we had going, of our silent agreement to endure together. Of something else between us, still unspoken.

“Don’t worry,” I said, stepping toward her. “I’ll convince him to let me wear it.”

“How are you planning to do that?”

“I’ll figure it out,” I told her. Then I added quietly, moving closer, “Sweet talk and dirty talk are the same with him, I’m guessing.”

She rolled her eyes. “You’re kidding me, right?”

I still wasn’t sure why she was upset. But at least she was paying attention. Maybe it meant she cared. I felt bolder. I lingered there, near enough to breathe her in, her scent like what I imagined mornings could be.

Claudia took a step closer. Eyes on me, she ran the fingers of her right hand once along the brim of my cap. Then, glancing toward the door of the kitchen to check if anyone was coming in, she lifted the brim, bent over a little, and kissed my cheek.

It felt as though she was saying goodbye, and I would need to convince her otherwise. But before I could try, the door swung open, and one of the cooks strode in, coffee in hand.

“Ladies,” he said in greeting, and went to hang up his jacket in the closet.

We shuffled away to start the morning prep.

◊

Eventually, Claudia ended up cutting her own hair so short she’d have no reason to use a hairnet either.

The manager left her alone after that, though I wondered again if the job would be hers for much longer.

“You’re lucky he doesn’t have a thing for tomboys,” I said to her, winking, as we stood at the six-burner stove. We were frying eggs and bacon, and the scent and the heat from the pans coated our skin.

She leaned closer to me.

CLAUDIA

We shared our breaks together, Eva and me, out back behind the diner.

One afternoon, in the chill November air that always makes me think of taking shelter, I mentioned I was grateful for the steady work.

Eva reached into her pocket for another cigarette. “You really think this job is something you need?” she said. “You’re a fool.”

“Sorry.”

She took her time while she lit up. “Why do you apologize so often?” She glared at me, blowing smoke. “You’re not queen of the world. You’re not so important everybody thinks you’re to blame.”

We rested against the brick wall in the shadows under the fire escape, shifting our weight from one tired foot to the other. My thoughts turned in tight circles. Something urgent about Eva always made me feel both so wide and so narrow.

“Don’t settle for this,” she said, looking around, as if her attention was drawn to something more important.

I couldn’t stop watching her.

Eva took off her baseball cap, and her muddy red curls came loose from the clasp where she’d tied them back. They fell around her face like a tattered wreath and tangled with the blue bandana knotted at the divot of her collarbone, the one she used to wipe her face in the heat of the kitchen.

What did life taste like to her? I wondered.

She looked back at me, and I quickly dropped my gaze—first to my old shoes, then to the cigarette I dropped to the ground and covered with the weight of my heel, then to the brick wall a few feet away from where we stood, pocked and lined with grit and dust. I tucked both my hands into the pockets of my jeans so she wouldn’t see how they were shaking, but then Eva leaned in and let me put my arms around her instead.

There’s a thin scar running halfway across my cheek that I got as a kid, from falling in a race. An ordinary mark I used to imagine as evidence of a battle. Eva reached up to touch it with the edge of her tongue, softly, just tenderly enough to be almost more than I thought I was ready for.

◊

Most of the things I learned about Eva were things I wasn’t expecting. Mostly, she just kept me guessing.

Only after a year in the kitchen did I find out she was already planning her getaway. “If we just worked here part time, to pay for something like college,” she said, “it w

ould be different.”

I didn’t really know what that difference meant. High school was all I thought I’d be able to get. This job was all I needed because it was all I knew I could do.

But Eva had me dreaming wild. I began to think about going to George Brown, to become a chef in a serious kitchen. I even considered applying for a student loan. I knew debt could be a trap, but I was caught by how much Eva wanted something more, by the need she had to go.

I gave her my charm bracelet for her birthday that year. Each of the little planets in our solar system hooked to its links, metal flawed from miniature half molds, the sharp clasp rubbing blue veins I saw pressed against her skin when she turned the inside of her wrist toward me. Each part of the dangling universe painted silver and gold, shivering in the air, swinging in her clipped shotgun salutation, casual, knees and arms blossoming bruises, bad-luck violet.

How hungry we were then. A storm of coffee and nicotine on her lips and mine, only eating enough when we were working. Taking something here and there on the side, the pies we divided to devour. Our hands touching underneath the table on lunch breaks we now spent in the sticky vinyl-seated booth at the very back of the dining room. Hauling ourselves up to work again, heated by the kitchen. Ringing the cutlery in the big wash bins as if we were trailing a flurry of wings of knives and forks, to drown out the sound of that world, get liftoff.

At night, I studied the ragged rash around the tattoo across her hip as if it were a book, new ink injected into tender skin. What I wanted badly enough, I was just beginning to understand.

◊

I thought I could handle being in that kitchen. It helped that you don’t have to be pretty there, don’t have to serve yourself up. The pay is regular so you keep going, and eventually you get faster and more able. Sooner or later, there’s less treading water, less threat of being pulled under.

Swimmers in Winter

Swimmers in Winter